Does your life have zero stress? Didn’t think so. The world is loaded with pressure, pain, trouble and strain. We all feel it—at different rates, for different reasons and with different outcomes. Yet some people are better at responding to life’s trials than others.

How do some people cope with adversity in a way that better positions them for success in life, while others appear more struggling or stuck?

The answer to this question is related to Stress Tolerance and Resiliency. This blog will explore these attributes together because when we break them down into skills, they are inextricably connected. Simply put, Stress Tolerance is withstanding life pressures, while it’s counterpart, Resiliency, is springing back after failure. Both skills—whether in resisting or in rebounding—contend with stress.

THE SIGNIFICANCE & SCOPE OF STRESS

People use the word “stressed” to describe their reaction to a wide range of situations—from getting caught in traffic, to changing jobs, to the loss of a loved one. Best known for his work on coping, cognitive psychologist Richard S. Lazarus, defines stress as “a condition experienced when a person perceives that the demands placed on them exceed the resources the individual has available.” Here is a simple variation: “Yikes! So much to do and so little time.”

Most of us realize when and why we suffer from stress, but it is more difficult to quantify how much stress we’re enduring. The Holmes-Rahe Stress Inventory was developed to help gauge the stress level experienced by an adult in the past year (there is a modified scale for non-adults). This instrument has limitations in that it doesn’t account for individual variables such as genetic makeup, current habits, age or outlook on life. Also, since people don’t often experience major life events, a better measure of stress might be the Daily Hassles and Uplifts scale which rates the seemingly inconsequential effects of everyday stressors. Small steady stresses can have more of a “straw that broke the camel’s back” effect because they accumulate slowly and go unnoticed until the point of sudden overload.

When you feel stressed by something, your body reacts by releasing “fight or flight” hormones, such as adrenaline, into your blood to produce more strength, energy or focus. This can be a good thing if the stress is caused by physical danger. But this can be harmful if it is a response to something emotional and there is no outlet for this extra energy and strength. Emotional stress that stays around for weeks or months can weaken the immune system and cause high blood pressure, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and even heart disease.

TWO “STRESS BUSTER” SKILLS

Stress will always be a part of life—protecting and plaguing us in turn. The good news is that there are healthy, positive skills that you can develop to keep stress from getting the better of you. Below are the two skill categories that enable us to cope with stress and adversity and bounce back.

STRESS TOLERANCE

Stress Tolerance is the capacity to endure pressure or uncertainty without becoming negative (e.g. hopeless, bitter or hostile) toward self or others.

People strong in Stress Tolerance can withstand and may even thrive in high-pressure situations. They effectively rise to the challenge of wrestling problems to resolution and smoothly undergo sudden trouble—say, when a deadline is moved up. Often productive and assured despite ambiguity, they cope with their worries and have space for people’s fluctuating emotions. Others may seek them out for their strength and look to them in times of uncertainty.

RESILIENCY

Resiliency is the capacity to recover positivity toward self and others—to rebound—after setback, difficulty or unexpected change.

People more inclined toward Resiliency can

maintain (or regain) functionality and vitality despite trouble or setback. They effectively combine strength and adaptability. Natural confidence and a positive outlook allow them to view difficulty as opportunity and failure as growth. They assume that their personal best is yet to come and don’t get stuck in disappointment. Instead, they envision the bright and assorted benefits that will result from the eventual attainment of their goals.

STRENGTH AND TOUGHNESS IN MATERIALS

Like people, material bodies also experience forces (loads) when they are used. We can better understand the interaction between Stress Tolerance and Resiliency by looking to the world of materials science.

Diamonds have been identified as one of the strongest materials on earth. The name comes from the Greek word adamas meaning “invincible” and is where we get the word adamant. The surface of a diamond is resistant to indentation, deformation or constant wear and tear. The problem with diamonds is that while very hard, they are brittle. If you smash a diamond with a hammer, it will shatter, proving that diamonds are not forever!

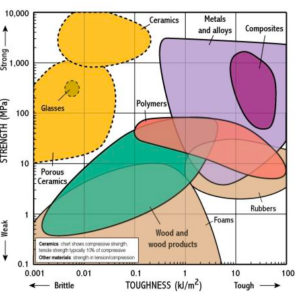

Rigid strength is clearly not the only attribute needed to effectively deal with stress. Materials that can absorb the strain of an impact, bend or twist—and spring back when unloaded—are considered resilient. Resilience is the restoring force by which a material is returned to its original shape and size. It is the “toughness” property that allows materials to bear shocks and vibrations. The greater the resilience of a material, the greater its practical capacity to perform.

As an example, titanium is a common material often used as part of the wing construction of giant aircraft. Titanium is both firm and flexible. No matter how hard a landing, it is unlikely to bend without returning. Wondrously strong and springy, titanium is softer than steel, harder than aluminum and tougher than almost anything else. Some call it “the most useful strong metal.”

Humans who are high in Stress Tolerance are also able to brace themselves under heavy stress. In all their strength, these individuals must pay attention to their limitations and not take on too much. They need regular times to rest and unload. A build-up of stress is detrimental to health and ultimately can cause people to crack or snap. But much will depend upon their level of Resiliency. Resilient people add flexibility to firmness; they are less brittle and tougher than others. But, USE CAUTION: extremely adaptable people are more inclined to exaggerate the positive and lose touch with what is realistic or lack urgency.

DIALING IN STRESS TOLERANCE & RESILIENCY

So how can you develop the optimal Stress Tolerance and Resiliency? Here, according to research1, are some powerful ways to help you become “titanium tough” in your ability to contend with life’s stressors. They are ordered according to the PAIRIN Imperatives progression as each skill relates to stress.

- Emotional Self-Awareness. Under pressure, when something difficult is occurring, emotions kick in. How do you know when you’re feeling stressed out or overwhelmed by what’s happening? Effective coping begins!

- Recognize when you are emotionally hooked: “I can’t stop replaying the conversation,” “My stomach is in knots,” “My jaw is clenched.”

- Slow down, take a breath and get curious about what’s really going on.

- Identify what you are feeling: “I’m in a shame storm,” “I feel _____ (embarrassed, hurt, resentful, fearful, lousy)” rather than offload on other people.

- Distinguish between feelings, e.g. disappointment and anger, shame and guilt, fear and grief… acknowledge and let yourself feel.

- Self-Assessment. Be ferociously reflective by asking yourself tough questions and answering honestly. Ask others around you too—friends, coworkers, your boss. Suspend the counterfactual stories you are making up and pursue accuracy with questions such as:

- What exactly is causing me distress?

- What does this situation mean? How will it affect me?

- What are my other options?

- How is my self-talk helping or hindering me?

- What reinforcements do I need? What don’t I need?

- When will I need to seek help? From whom?

- Is it time to unload and rest? (see below)

- Self-Alignment. All of us fight battles against not being good enough and not belonging enough. Strive to maintain a separation between your identity and the cause of your temporary stress or trauma.

- Look within for satisfaction and not to external things and circumstances.

- Wholly accept who you are at your core; at the same time, radically evaluate how you are so as to improve. “I am enough.” “My planning can improve.”

- Do not inflate your sense of self or put yourself at the center of every situation.

- Self-Confidence. Build confidence in your ability to respond to stress or setback.

- Recognize that you have been through difficult experiences, some more difficult than others. You’ve survived all of them so far. Confidence naturally builds as you come through trials.

- Recall and rely on the skills you have built over time. The more you practice these skills, the better you will become.

- Face stress head on and learn how and when to use the following coping techniques: Avoid unnecessary stressors, alter the situation, adapt yourself to the situation or accept what you cannot change.

- Set realistic goals and seek help to address insecurities.

- Self-Blame. A dash of healthy humility moderates over-confidence. Meanwhile, be sure to reality-check the inner critic that drives the “never good enough” messages.

- Learn to celebrate what “is” (the good) more than belittle yourself for what is “not.” Research2 suggests that for every negative emotion we endure, we have to experience at least three heartfelt uplifting emotions.

- Rather than belittling and sabotaging yourself, seek to view every stressful situation as a “learning opportunity.”

- Deal with the past so as not to allow emotional baggage of the past to weigh you down.

- Self-Restraint. Practice appropriate—not over or under—restraint and control.

- Let go of overcontrol, and you will often lessen the pressure you’re under. Stick to controlling your actions and responses, not what others do and think, not outcomes, not the weather, stock market, workplace or the world. Speak openly about pressures and failures. Don’t suppress your emotions and allow them to stockpile.

- On the flipside, refrain from impulsive responses to stress. Don’t excessively double down and over function; don’t avoid, numb out or shut down and under function.

In addition to the above foundational skills, Stress Tolerant and Resilient people find strength in two more important ingredients:

- Body-care. Find physical outlets for your stress. Without this, you can become tired, frayed and unhealthy. Learn to say “no” to ensure you make time to tend to your exercise, sunshine, diet, nutrition, and sleep.

- Soul-care. Cultivate hope. Hope is what keeps people going when all else is lost. Sometimes all we have left is hope. When the pressure is on, how can you stay hopeful? What is most important to you? Who is important to you? Practices like prayer and meditation feed your soul with love, joy, peace, compassion, and gratitude. Find a small group of friends and allies with whom you “do life,” eat, work, play; people who know your story and will fight for your heart.

REFLECTION

Now let’s put it all together. Recall a stressful situation that you believe you coped with positively. With this in mind, read through the above steps. What factors did you use from the list to facilitate your success? How were you able to tolerate and grow through the experience?

Now, consider some of the major life failures or setbacks you have experienced. Can you identify differences in how you appraised these events? What were the key ingredients that enabled you to bounce back from these events?

CONCLUSION

How we deal with adversity and stress strongly affects how we succeed, and this is one of the most foundational reasons for developing Stress Tolerance and Resiliency skills. Remember that not all stress is bad. A healthy amount of stress (and when managed appropriately) can help us become stronger and learn future coping mechanisms. Yes, there will be times when we will falter and occasionally fall flat on our faces. The only way to avoid this is to never try anything new or take a risk. The choice is up to you. Do you want to strive for Resiliency—that “titanium tough” blend of Stress Tolerance and flexibility?

References

For more information and strategies on building stress tolerance, check out this blog.

- Suniya S. Luthar, Dante Cicchetti, and Bronwyn Becker, “The Construct of Resilience: A Critical Evaluation and Guidelines for Future Work,” Child Development 71, no. 3 (2000): 543–62; Anthony D. Ong, C. S. Bergeman, Toni L. Bisconti, and Kimberly A. Wallace, “Psychological Resilience, Positive Emotions, and Successful Adaptation to Stress in Later Life,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 91, no. 4 (2006): 730–49. 3. C. R. Snyder, Psychology of Hope: You Can Get There from Here, paperback ed. (New York: Free Press, 2003); C. R. Snyder, “Hope Theory: Rainbows in the Mind,” Psychological Inquiry 13, no. 4 (2002): 249–75. 4. C. R. Snyder, Kenneth A. Lehman, Ben Kluck, and Yngve Monsson, “Hope for Rehabilitation and Vice Versa,” Rehabilitation Psychology 51, no. 2 (2006): 89–112

- Barbara Fredrickson, PhD, the author of Positivity (Crown Archetype, 2009).