How often do you see things with flashy “innovative” titles out in the market and your first response is to get curious and want to buy, use or consume that thing? Is your first reaction to be skeptical or excited? If it’s excited, you’re not alone. That’s the reason behind the use of those phrases. But, using the newest, flashiest thing usually isn’t the best thing, especially depending on it’s intended use. Ideally, it’s better to use the right tool for a job, not the newest or most interesting.

Why are we attracted to the new and flashy like cats to sparkly toys? It all comes down to how our brains function. Evolutionarily, those who responded quickly to things happening around them survived longer and passed their DNA along. And for things to happen quickly in your brain, a lot of those things have to happen pretty automatically and outside of your awareness to keep your conscious mind from slowing things down with all the messy thinking and analyzing it can do. So, we basically have two major parts of our mind: a very quick, automatic, unconscious mind and a slower, more critical thinking mind. They both have important functions, but we need to be able to engage the right parts when they’re really needed.

Robert Cialdini wrote about Six Principles of Persuasion in his best-selling book, Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. His principles are tied to what he refers to as the “click, whir” part of our brains, and that’s really accurate for our automatic mind. When something triggers that part of your brain, it starts flipping levers and switches in your head to get you to do things. One principle that applies here is the Principle of Scarcity which Cialdini defines as the more scarce you believe a thing is, the more you’ll want it before your thinking brain can even calculate real value. That’s because, from an evolutionary perspective, scarce things are the difference between life and death, so your brain wants whatever it believes to be scarce. Also, Cialdini’s Principle of Social Proof is especially powerful here, which states that we’ve found over time that people who stand together are more likely to survive than people who stand out. Therefore, we like to be like other people. We naturally want to be part of the crowd, not those who stand apart from it. When confronted with new and improved, flashy things there is a fear of missing out because we “know” others will want to use them. So, instinctively we want to use them as well, and preferably, before everyone else.

Robert Cialdini wrote about Six Principles of Persuasion in his best-selling book, Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. His principles are tied to what he refers to as the “click, whir” part of our brains, and that’s really accurate for our automatic mind. When something triggers that part of your brain, it starts flipping levers and switches in your head to get you to do things. One principle that applies here is the Principle of Scarcity which Cialdini defines as the more scarce you believe a thing is, the more you’ll want it before your thinking brain can even calculate real value. That’s because, from an evolutionary perspective, scarce things are the difference between life and death, so your brain wants whatever it believes to be scarce. Also, Cialdini’s Principle of Social Proof is especially powerful here, which states that we’ve found over time that people who stand together are more likely to survive than people who stand out. Therefore, we like to be like other people. We naturally want to be part of the crowd, not those who stand apart from it. When confronted with new and improved, flashy things there is a fear of missing out because we “know” others will want to use them. So, instinctively we want to use them as well, and preferably, before everyone else.

The unconscious thought processes that Dr. Cialdini talks about tend to be very useful for making quick, life and death decisions but not as good for making strategic decisions. Basically, the unconscious mind relies on using “rules-based thinking,” which is defined as a complex process map filled with “if-then” statements. If someone understands how this process map works, it can be exploited by using those rules to make expected decisions. That’s why Dr. Cialdini’s book is subtitled, “The Psychology of Persuasion.” If one understands how this map works, then persuasion of others becomes easier.

The Fight-or-flight response is a good example of the automatic processes of the unconscious mind. It relies on features to make decisions about whether to fight or run. Does the thing that’s being encountered have pointy teeth? Is it bigger than me? Is it faster than me? Answers to those questions cause near-immediate reactions. After an encounter, you might hear people talking about how they might have reacted differently had they had time to think. That’s the conscious mind evaluating the decisions made by the automatic mind.

The unconscious mind is also where our stereotypes and biases reside. This isn’t really surprising when you think about the fact that automatic processing is features-based. It looks at the features of a person or an object and makes quick decisions about likely actions. However, there are insights that can be taken from bias-training that can be applied here. Bias-training tells people to make sure to let their controlled thinking supervise their automatic thinking. While automatic thinking occurs quickly and outside of our awareness, we can be aware of the actions our automatic minds want us to take. If you encounter someone and instantly feel like you should take a certain action, you can use your conscious to ask key questions to alter and override your actions.

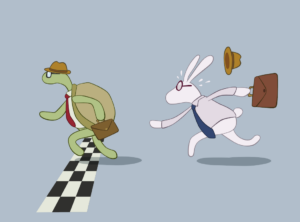

The battle between your automatic and controlled thinking can be compared to an old fable about the tortoise and the hare. Your automatic mind is symbolized by the hare as it desperately wants you to make all of your decisions right now. Your controlled mind is the tortoise that wants to take it slow and make decisions in due time. So, if you are familiar with that fable, you know it’s a good idea to pay attention to what the tortoise wants. So, Stop. Slow down. Give your brain time to think and really consider all of your options.

The battle between your automatic and controlled thinking can be compared to an old fable about the tortoise and the hare. Your automatic mind is symbolized by the hare as it desperately wants you to make all of your decisions right now. Your controlled mind is the tortoise that wants to take it slow and make decisions in due time. So, if you are familiar with that fable, you know it’s a good idea to pay attention to what the tortoise wants. So, Stop. Slow down. Give your brain time to think and really consider all of your options.

Another method for your controlling your thinking is to build more facts around what you may be trying to make a decision about by creating a concrete list of pros and cons. If something is truly improved, how much has it improved? On what metric? Will the improvements actually equal return on investment that will be worthwhile? Essentially, what you want to do is slow your automatic decision making and give your controlled brain a chance to engage in critical thinking. Don’t be the hare and rush to the finish line; be like the tortoise, and take your time to make your decisions using all of the facts and information at your disposal to arrive at the finish line precisely when you’re ready.

My grandfather used to love the old adage, “If something seems too good to be true, it probably is.” And that’s particularly apt in the discussion surrounding your automatic and controlled minds. When you suddenly feel like something you’re being sold is relying on your automatic processes and telling you to make a decision “right now,” that’s a good indicator to slow down, take your time and think about all aspects of the decision.

Be the tortoise and take your time, keeping the hare from getting to the finish line too quickly.