If you’ve been keeping up with our blog series about what to expect in the future as we move into the post-COVID-19 era, you know to expect remote work to stick around in some form. The pandemic forced organizations to overcome the challenges of being in-person to survive and now they’re seeing that maintaining a remote workforce makes sense. But, could we see the same thing in Education? Academic institutions from K-12 to higher education experienced a variety of new challenges as the COVID-19 pandemic took control. Schools closed, and there were drastic attempts to facilitate remote learning to keep kids and adults engaged, while also trying to balance keeping everyone safe.

Now that we’re almost a full year after the COVID-19 pandemic forced us to change our behaviors drastically, what is the future of education in 2021 and beyond? Several factors play into the answer to this question.

K-12 Education

One key factor is how successful online learning has been in educating students. Most experts agree that it’s not worked very well, especially for younger students and those from lower socioeconomic statuses. Earlier in the summer of 2020, learning losses for K-12 students were examined using three possible scenarios (return to in-class schooling in Fall 2020, Jan 2021 or Fall 2021) and made dire predictions that could equate to 7-14 months of lost learning due to COVID-19, school closures and differences in quality of remote instruction.

With those predictions and a great deal of confusion around criteria to safely reopen schools, there has been a range of school reopening conditions between orders to reopen all schools to partial or complete closing remaining in effect. However, the bulk of states (40) have no order in effect, leaving reopening decisions to local officials.

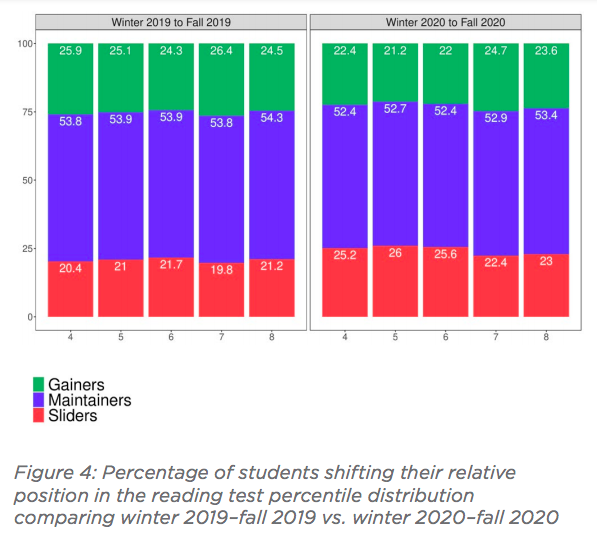

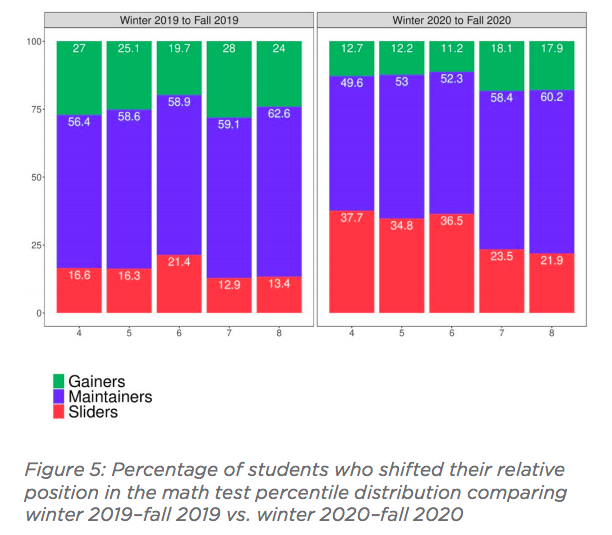

The conditions related to COVID-19 and disparate school reopening plans created measurement challenges related to student learning attainment. However, in Fall 2020, NWEA administered remote MAP assessments to 4.4 million U.S. students in grades 3-8. NWEA, formerly known as Northwest Evaluation Association, is a nonprofit focused on supporting students and educators through assessment in more than 9,500 schools, districts and educational agencies. MAP assessments are designed to measure students’ reading and mathematics attainment and are regularly used to benchmark student progress, so they’re ideal for examining deficiencies. In general, results showed that students performed similarly to those from 2019 in reading, but were about 5-10 percentile points lower in math skills. This led to the conclusion that more students were falling behind in their learning relative to previous standings.

As shown in this chart, in comparison to previous years, students showed similar patterns of “Gainers” (those who moved up one quintile), “Maintainers” (those who stayed in the same quintile) and “Sliders” (those who moved down one quintile).

However, for math, Sliders were considerably higher across all grades, reducing the number of Gainers. In addition, reports pertaining to student mental health suggest other challenges, such as 46% of teachers reporting an increase in their students’ significant mental health issues like anxiety, depression, trauma and grief.

While remote learning for these young students is a better option than no instruction at all, young people are in a fragile position where they’re not just learning math and science but also learning how to interact with each other by developing the social skills and essential (soft) skills they’ll take into adulthood. Remote learning is an unlikely analog for acquiring those skills. Several organizations are being forward-thinking and looking beyond the end of the pandemic to explore ways to bring schools into the centers of their communities, making them a focus for local industries and organizations and identifying local allies to shore up and support schools. Others urge that the critical problem to be solved is a leadership problem whereas local and national political and academic leaders should work in powerful ways to eliminate inequalities in the school system. For example, they urge the FCC to be more forceful with its Lifeline program to create universal internet for every United States household. Had that program been in place, the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on the American school system would have been blunted considerably.

Some states are even proposing legislation that will better connect high school students — especially those farthest from opportunity — to high quality career pathways careers and other postsecondary opportunities. For example, PAIRIN is a supporter of the State of Colorado’s proposed “Successful High School Transitions (SB21-106)” that seeks to creates greater flexibility around requirements that students learn within the walls of the traditional classroom, allowing a wider range of career and postsecondary opportunities, and makes the fourth year of high school more meaningful. Eligible students who complete high school in three years would receive funding to take full-time college courses or participate in career training in their fourth year of high school—saving them time and money.

The critical piece to remember is the core of education is Learning. While the COVID-19 pandemic has been terribly difficult for the K-12 education system, we have the opportunity to learn from it. We can learn what was most challenging and as more schools open up and vaccines are administered to teachers, we can establish the leadership needed to make changes that will protect our children if something like this happens again. And we can address systemic inequalities in the education system that have always been in existence that the pandemic showed a spotlight upon.

Postsecondary Education

While K-12 students are more likely to head back to in-person learning that is more similar to what they were used to before COVID-19, the same can’t be said for postsecondary education. There has been a great deal of conversation and research into improving what postsecondary students may need going forward from higher learning institutions.

Looking ahead, McKinsey experts propose a set of essential principles to guide the next phase of higher learning:

- Focus on access and equity – Similar to students in the K-12 system, some postsecondary students struggle with doing remote learning due to disabilities and/or socioeconomic challenges. Institutions must work to increase access and equity for those students.

- Support faculty – Teachers were leaving the education system even before COVID-19 due to stress and other factors, which has increased as a result of the pandemic. Institutions must create the structure to support faculty by providing them training and ways to collaborate and share best practices.

- Create an online “quad,” or central university courtyard – Even though postsecondary students aren’t as affected by the lack of social interaction as K-12 students, it’s still essential to provide them ways to feel the vibrancy of the in-person college experience. Institutions are already starting to create online “student plazas” and “virtual homerooms.”

- Activate stakeholders – Universities are rich in talent related to technology, remote learning and work. A key for postsecondary institutions is to tap into the students, alumni and communities around them for talent and resources to build the tools and resources they need.

- Invest in cybersecurity – Everything is going online, and cybersecurity is necessary for any remote efforts. It’s essential to make remote learning and socializing as secure from cyberthreats as possible.

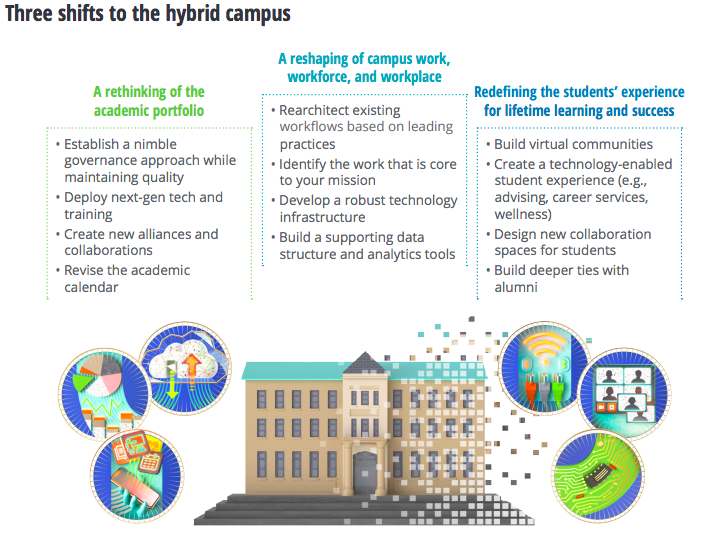

This major shift for postsecondary education is toward a model called “the hybrid campus.” An older concept in education–blended learning–involved students completing a portion of their education in the classroom and the rest from online sources. The hybrid campus differs from blended learning in that the goal is to create a holistic academic experience for students. So, students will be able to learn in the classroom, engage in online settings and be able to access things like academic advising and career services in both modalities. Deloitte outlines three ways to shift to a hybrid campus, as shown below.

Several universities were already working toward the hybrid campus before the COVID-19 pandemic, including Georgia State University, Duke University, Arizona State University, University of Central Florida and the University of Michigan. Those institutions were able to react to and adjust to the pandemic’s demands without feeling the effects as severely as other universities. So, this move to the hybrid campus is more critical as we move forward to lessen the impact of pandemic recovery and create a more resilient system for future emergent conditions that may affect the system.

Moving Forward

The education system has struggled greatly with the COVID-19 pandemic, but it’s survived, and it’s learning and adjusting as we go. Author Josephine Hart is quoted as saying, “Damaged people are dangerous. They know how to survive.” This can be applied to the current status of our education system. It was hit hard by the pandemic, but I’m confident that it’s going to come back even more potent because centers of learning always do just that.

They learn. They grow. They adjust. And as long as they keep the success of students at the center of the process, our student’s future will be bright.